a no-win proposition: how small schools hurt the big-school bottom line

Recently, the crew here at re-mediating assessment has been thinking and talking about the affordances of small schools. Specifically, we've been talking about alternative schools, with their smaller populations, greater flexibility, and targeted instructional techniques.

Recently, the crew here at re-mediating assessment has been thinking and talking about the affordances of small schools. Specifically, we've been talking about alternative schools, with their smaller populations, greater flexibility, and targeted instructional techniques.When I say "alternative," I want you to think alternative as in "an option other than the big public high school" and not as in "an option other than going to juvenile detention." In particular, we've been working with Becky Rupert, a teacher at Aurora Alternative High School, in Bloomington, IN. We've had roaring success working with her and her students, and we've been talking about expanding our work to multiple alternative or small schools in Indiana.

Now, however, comes a report out of New York City that the small schools movement there is causing larger schools to struggle to accommodate the needs of a shifting student population. According to the report, which was developed by New York's Center for New York City Affairs, the small schools movement was a key initiative embraced by Mayor Bloomberg as an effort to serve students at failing high schools. The city has closed over two dozen large high schools in the last seven years, replacing them with smaller schools.

While students at those smaller schools showed strong increases on achievement, many students from the closed schools simply moved to other large public high schools in the area. Whereas the smaller schools were able to provide individualized attention and target learning deficiencies, the larger schools--often already ill equipped to meet the needs of its student body--was unable to accommodate the increased population of struggling learners. As a result, attendance and graduation rates have dropped at the larger schools.

People are going to be tempted to use this study to prove one of the following assertions:

- Small schools are meeting student needs more successfully, and we should therefore try to replace as many larger schools as possible with the smaller, more personalized alternative;

- Small schools are hurting more students than they are helping, and we should therefore close them down and invest that money in larger public schools.

Neither of these arguments is right. This is not an either/or proposition, and turning it into a black-and-white issue does a disservice to the complicated field of teaching and learning. The truth is that while small schools may raise achievement on accountability measures--standardized test scores, attendance and graduation rates--there are indications that this comes at the expense of some other key learning opportunities. Small schools cannot, for example, offer the variety of courses that larger schools can provide; they often lack extracurricular opportunities such as sports teams, clubs, and academic organizations; and while they may offer comparable technological resources to those offered at larger schools, small schools are less likely to contain the range of adult expertises that allow the technologies to be leveraged for a range of participatory experiences.

Neither of these arguments is right. This is not an either/or proposition, and turning it into a black-and-white issue does a disservice to the complicated field of teaching and learning. The truth is that while small schools may raise achievement on accountability measures--standardized test scores, attendance and graduation rates--there are indications that this comes at the expense of some other key learning opportunities. Small schools cannot, for example, offer the variety of courses that larger schools can provide; they often lack extracurricular opportunities such as sports teams, clubs, and academic organizations; and while they may offer comparable technological resources to those offered at larger schools, small schools are less likely to contain the range of adult expertises that allow the technologies to be leveraged for a range of participatory experiences. At the same time, large schools that come equipped with the above still often lack the ability to meet the needs of the broad population that they serve. Instruction tends to target a "typical learner"--the type of student who can do well on state-mandated test, given proper instruction; who will do moderately well in one or two AP classes; who will graduate with a 3.4 grade point average, one internship, and plans for college. Large schools can't direct instruction toward the specific interests, needs, and values of its student body, and all the extracurricular opportunities and Zulu classes in the world won't make a difference to the overlooked and underserved students of these bigger institutions.

At the same time, large schools that come equipped with the above still often lack the ability to meet the needs of the broad population that they serve. Instruction tends to target a "typical learner"--the type of student who can do well on state-mandated test, given proper instruction; who will do moderately well in one or two AP classes; who will graduate with a 3.4 grade point average, one internship, and plans for college. Large schools can't direct instruction toward the specific interests, needs, and values of its student body, and all the extracurricular opportunities and Zulu classes in the world won't make a difference to the overlooked and underserved students of these bigger institutions.The solution is somewhere in the middle, though don't ask me where the "middle" is. The answer is not to simply close down both large and small schools and replace them with "medium" schools. The answer is not to open up city-sponsored afterschool programs for all learners. The change that must occur is something much deeper.

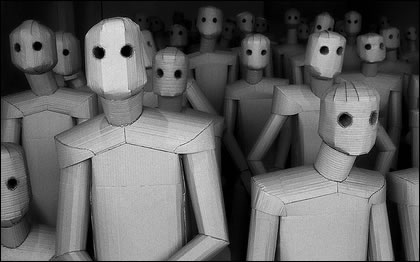

In truth, as the product of a sprawling public high school that served 5,000 students, I lean more toward the value systems embraced by and possibilities inherent in many small schools. A more careful, more measured, more personalized approach to instruction is strides away from the factory model of education that lingers from the early days of compulsory education in America. As I think we can all agree, the last thing we need is more high school graduates equipped for a career in the factories that, for the most part, no longer even exist.

In truth, as the product of a sprawling public high school that served 5,000 students, I lean more toward the value systems embraced by and possibilities inherent in many small schools. A more careful, more measured, more personalized approach to instruction is strides away from the factory model of education that lingers from the early days of compulsory education in America. As I think we can all agree, the last thing we need is more high school graduates equipped for a career in the factories that, for the most part, no longer even exist.

0 comments:

Post a Comment